This is David Angaiak’s first Cama-i. It’s also his first show as an artist. He’s always been an artist, but he gave up his day job five years ago and made creating art his full time job. That’s when he started making tegumiat, or dance fans. He set them up for the festival in a long hallway with dozens of foldable tables, along with all of the other vendors in town for the annual dance festival.

Angaiak’s wife bought fur boot toppers from the lady beside them, who had qaspeqs and fur patches for kids to touch. Across from them a man had a table cluttered full of ulu knives. Angaiak’s table display included line drawings alongside blue and green wooden handles crowned with spreads of goose feathers. Dance fans, and dancers, are on full display during the festival. Angaiak said that there are subtle differences between them if you know what to look for.

“Male fans are gonna have a longer, broader feather and they span out. There's actually a number of different styles. What's really popular right now is the five-feather and the six-feather style. And for ladies fans, they're a little more delicate,” Angaiak said. “A lot of times, households will actually have designs that are kind of generational.”

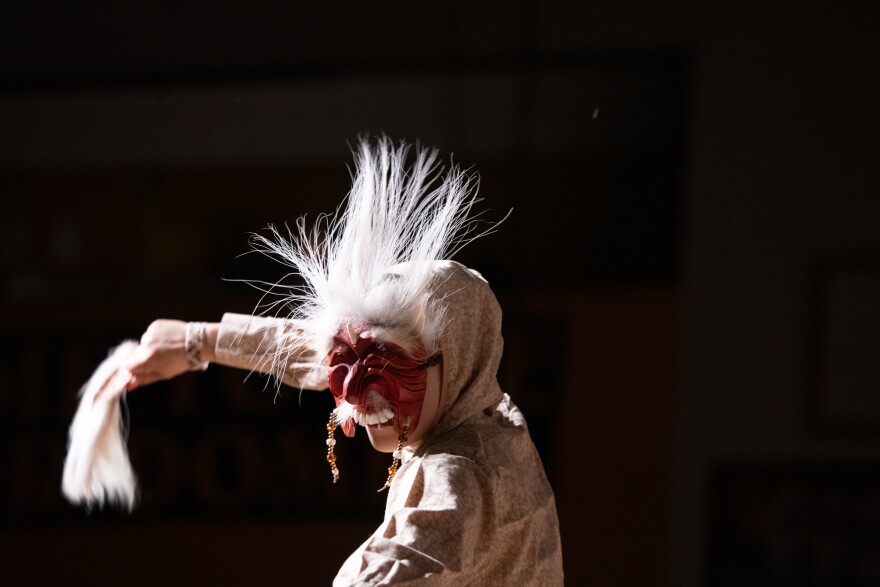

Angaiak also makes masks, which are paired with the dance fans for traditional storytelling dances.

“When I create story masks, I make them functional. Not just something that you'd hang on the wall, because they weren't designed to be on the wall,” Angaiak explained. “A lot of times today you'll see, you know, maybe you're in Anchorage, or you're in a city, or in a museum, and you see the mask, and it's on the wall. And it's kind of misleading, because the whole purpose of the story mask was to convey these stories, you know, or to lift up prayer.”

Angaiak is Yup’ik. His dad is from Tununak on the northwest side of Nelson Island. His mom is from Bristol Bay, where he grew up too. He doesn’t speak Yugtun, but is trying to learn now. His parents lived in an era when tradition was taboo, and masks and the dances were banned in many parts of the state.

“At the time, missionaries coming to the region saw the ceremonies in the dance, and the wearing of masks, and the customs of our people as something not healthy, which I don't agree with.” Angaiak said. “I'm Christian, but I don't agree with that view.”

Angaiak said that his grandfather had carved and made fans, but his dad didn’t learn until he was in university, where he took an art class as part of Alaska Native studies in the 1980s.

“And he came home one day and was like, 'I'm gonna make a mask,'” Angaiak said. “And I was so little, I think I was maybe eight years old, and I didn't really understand. Because at the places we went to, we didn't see masks. And so, anyway, he started making a mask.”

That was the beginning of Angaiak's journey exploring this part of Yup’ik culture. He said that the questions came fast.

“Oh, well, what else? What else am I missing? Like, what can I do? And how can I be a part of this,” Angaiak said.

Angaiak never made a mask with his father, though they did line drawing together. But as time went on, he wanted to dive into Native arts that were functional too. He makes masks that people can use seamlessly during dances, with a knob on the inside for the dancer to grip with their mouths.

“Masks weren't worn with straps or a head strap. You literally would just pick them up with your teeth,” Angaiak said.

That makes it easier for dancers to put it on while undergoing their transformation.

“You know, and because it was instantaneous, you didn't have to see them tying anything,” Angaiak said. “They were able to go right into the song, into the end of the story, or into the prayer.”

Differences in the masks symbolize differences in characters. Angaiak said that an upturned mouth symbolizes the female; a downturned mouth is male.

“A lot of times, you'll see appendages attached to the masks where there's hoops. And the hoops sometimes represent the universe. There's layers. Kind of think of it like in the Christian world: there's heaven, there's Earth, and there's hell; maybe like heaven, earth, and the underworld. It’s something similar in the Yup'ik world,” Angaiak explained.

Angaiak insisted that he couldn’t explain too much about how the storytelling works within the dances because he’s not a dancer; he crafts their tools. But as he’s contributing to a culture he’s trying to dive deeper into, it’s also his art.

“It's a little bit of me, with the mask. Absolutely. You know, it's an intimate process, and the outcome of it is exciting,” Angaiak said. Just recently, a friend of mine, she had let me borrow the mask that I had made to use at a show. And when I saw it, it was like, reunifying, like, the best way to describe it was when you see friends or family again after a long time away.”

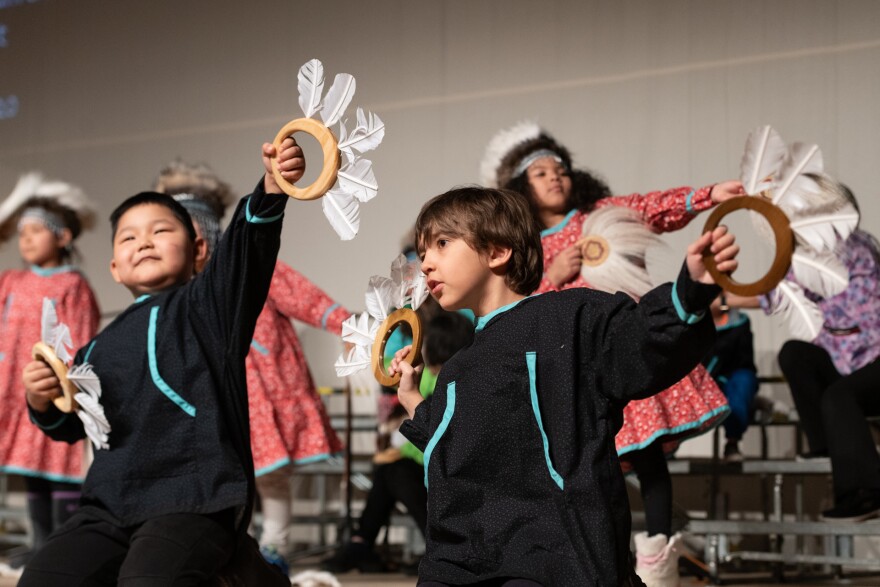

A number of dancers bought Angaiak’s dance fans over the weekend, and some are using them during the festival. Maribeth Herron bought a pair for her son, Charles Jr., who performed his first dance on stage this weekend.

“The reason why I got them is because they mean a lot to me and my culture,” Herron said.

She said that she was drawn to how pure Angaiak’s designs were, how they fit the hands, and how they were made with natural materials and dyes. They sell for $350 to $400 a set.

“It's made out of material from the land and the animals. And I think it's like an extension of the culture, in my opinion,” Herron said.

Both Herron and her husband, Charles Sr., danced growing up, and seeing their son on stage with his first dance fans was a moving experience.

“It was so emotional,” Herron said. “It was exciting. I was happy for him. I felt like, you know, I felt what he felt. My eyes welled up a little.”

All day, kids approached Angaiak’s table, gawking at the sets with blue and orange handles. Many picked them up and tried them out, others grabbed their parents in fleeting hope. Others, with luck, got their own pair this weekend.

“For me, coming here and seeing the children go by and pick up my dance fans, and test them out and play with them, it just melts my heart,” Angaiak said. “And, you know, I got to see a young man dance with them last night. And that, that's what this is all about.”