President Biden entered office a year ago in the thick of a deadly pandemic and with Washington still reeling from an attack on the Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump.

On the anniversary of Biden's inauguration, the United States is facing yet another massive wave of COVID-19 cases, and the country remains deeply polarized.

While the central crises have remained constant, Biden has pushed ahead on his priorities — from ramping up vaccine distribution to addressing climate change — with varying degrees of success.

Here's a look at some of the defining moments from Biden's first year in office.

A premature declaration of independence from COVID

In the spring of 2021, things were looking up when it came to COVID. Millions of Americans had been vaccinated. In May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention even lifted mask requirements for fully vaccinated people.

Biden presided over a big Fourth of July celebration that was supposed to kick off a summer of getting back to normal.

"So, today, while the virus hasn't been vanquished, we know this: It no longer controls our lives," Biden said from the South Lawn.

But that "freedom" was short-lived. The delta variant was already spreading rapidly. By the end of July, the CDC had reimposed the mask requirements. Hospitalizations and deaths again soared.

The pandemic disrupted supply chains and contributed to soaring inflation. And then the highly contagious omicron variant hit, once again overwhelming hospitals and disrupting school schedules.

The pandemic continues to affect daily life for weary Americans — and to drag down Biden's approval ratings. "Some people may call what's happening now the new normal," Biden said on Wednesday. "I call it a job not yet finished. It will get better."

Chaos in Kabul

Biden stuck to his promise to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, ending America's longest war in August. But the withdrawal was chaotic, and scenes of Americans being evacuated from Kabul drew comparisons to the fall of Saigon.

The chaos was magnified when a suicide bomber killed 13 American service members and an estimated 170 Afghans. Compounding the tragedy, a U.S. drone strike meant to take out the masterminds behind the terrorist attack instead killed 10 civilians, including seven children.

Ultimately, more than 120,000 people were evacuated from Afghanistan in the weeks leading up to Aug. 31. Biden faced criticism from Democrats and Republicans alike for his handling of the Afghanistan withdrawal.

Still, Biden forcefully defended his decision. "I was not going to extend this forever war," Biden said in August, "and I was not extending a forever exit."

Biden has sought to turn U.S. foreign policy to China — part of why he wanted to exit Afghanistan. But he has been consistently distracted by Russia, first with cyberattacks and now as President Vladimir Putin appears ready to invade Ukraine.

Biden told reporters on Wednesday that "my guess is he will move in — he has to do something." Biden has threatened withering economic sanctions, though he admits it's hard to keep allies behind that strategy, which will hurt them, too.

Manchin sinks Build Back Better dreams — twice

After Congress passed a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package in March, Biden turned his attention to his sprawling plan to create jobs, fix infrastructure, shore up the social safety net and address climate change — a massive plan he had dubbed "Build Back Better."

It was a heavy lift, given the very slim majorities Democrats hold in the House and Senate — and Democrats themselves were split over the size and scope of the package. After months of negotiating, Biden went to Congress in October urging Democrats to get behind a slimmed-down $1.75 trillion social safety net and climate change package and a separate $1 trillion infrastructure bill.

It was on the eve of a major international climate summit in Glasgow, and Biden wanted to be able to show he could deliver on his promise to curb carbon emissions.

But while Biden was overseas, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin dealt a serious blow, saying he would not back the package that he complained was full of "shell games" and "budget gimmicks" and ignored concerns about government spending and inflation.

It wasn't the last time Manchin would block the bill. In December, he once again said he would not back it. And on Wednesday, Biden conceded that "we're going to have to probably break it up" and pass pieces of the bill in smaller "chunks."

"Finally, infrastructure week"

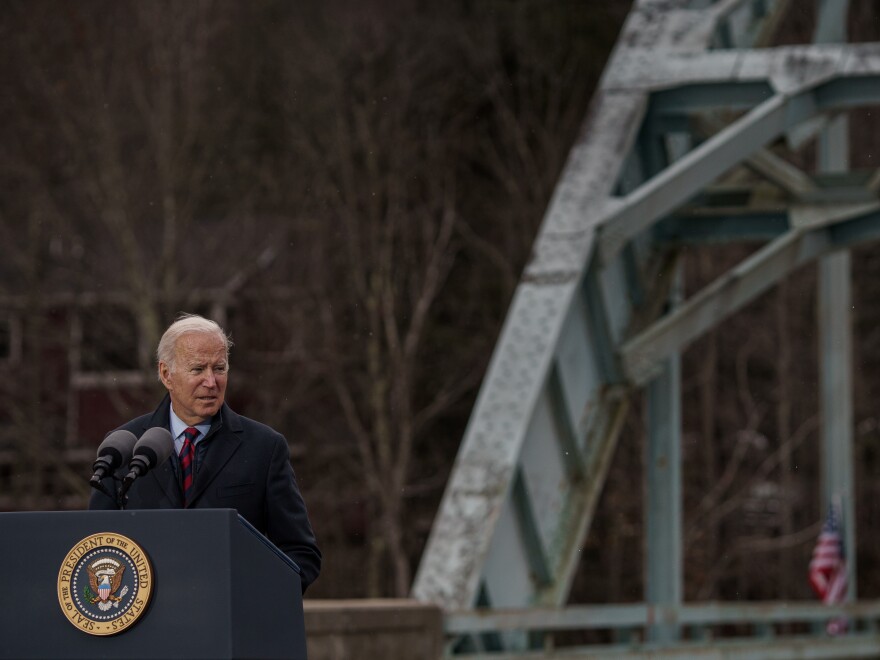

Despite all his legislative setbacks, Biden scored a rare bipartisan victory in November by securing $1 trillion in spending to rebuild crumbling roads and bridges, expand broadband internet access and get rid of lead pipes.

"Finally, infrastructure week," Biden said, chuckling over what had become a running joke about his predecessor, who had failed to make a deal despite often vowing to turn his attention to it.

It also gave Biden the opportunity to tout his bipartisan bona fides, as 19 Senate Republicans and 13 House GOP members backed the legislation.

In recent weeks the White House has been touting the new law as the government begins doling out funds to states and municipalities. These government-funded projects will likely be a big part of campaigns in the midterms this year and beyond.

In Tulsa, a moment of reckoning on race

Biden traveled to Tulsa, Okla. in June to mark the 100th anniversary of a massacre in the all-Black district of Greenwood by a white mob — and to talk about the inequities that persist in the United States today.

After the so-called racial reckoning of 2020, Biden pledged to redouble his efforts to address systemic racism and to make it a key part of his presidency.

His administration has ordered agencies to examine and address practices that may be discriminatory. The White House has also set a goal for more government contracts to be awarded to minority owned businesses.

The expanded child tax credit from the COVID relief bill dramatically lowered child poverty in Black households before it expired at the end of the year.

In his speech in Tulsa, Biden also talked about protecting the right to vote. It was there that he announced that Vice President Harris would be in charge of efforts to roll back state legislation that makes it harder to vote.

But voting rights bills in Congress have stalled. Facing pressure from activists, Biden made a forceful push to change Senate filibuster rules to allow the legislation to pass with a simple majority. And on the eve of the anniversary of his inauguration, he was unable to command the full support of Democrats to change the filibuster to make it happen.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.